We’ve covered grammar a few times in the past, but as I’m in the middle of writing the grammar chapter in my book, this might be a nice opportunity to go through grammar in some depth.

Grammar is a storytelling machine. It takes in a few actors, picks an action, and sets a story in motion. Every piece of obnoxious grammatical jargon (the pluperfect passive indicative, the genitive case, the subordinate clause) is just a different way to tell a story. And we tell all sorts of stories, which is why grammar books tend to be long. Even with just three actors – myself, dog, cookie – the possibilities are almost endless: I will feed my dog a cookie, My dog feeds me a cookie, A cookie fed me to my dog, etc.

Every grammatical story has a few necessary ingredients. We need to know the roles of every player in our sentence (I feed my dog a cookie, My dog feeds me a cookie), and we need to know precisely how, when and whether the action takes place (I feed my dog daily, I fed my dog last night, I would have fed my dog…).

Each of these stories has a different grammatical form, and while grammar has a lot of possible forms, it makes each of these forms using only three basic operations: it can move words (It is done -> Is it done?), it can change words (I eat hamburgers -> I ate hamburgers) and it can add words (You like cats -> Do you like cats?). Every single grammatical form is just a combination of one or more of these three operations.

So to learn grammar, we just need to break down each form we encounter into its components. On the surface, we’re just going to memorize a bunch of sentences, but because we’re breaking these sentences down into tiny, single-operation chunks, we can get a lot of mileage out of each sentence we encounter.

The procedure is relatively simple: First, find an example sentence. The easiest source for these is a grammar book, because it’s already arranged in order of complexity. Second, make sure you understand that sentence. You can use translations here; we’re going to get rid of them when we turn this sentence into flashcards. Within a couple of weeks, you’ll forget the translations and retain the meaning of the words and grammar in your target language. Once you’ve fully understood out the meaning of your sentence, you’ll learn the basic vocabulary, learn any changes in word formation, and learn the word order.

Let’s go through an example:

- Find an example sentence: I fed my dog a cookie.

- Make sure you really understand it. Who’s doing what to whom? When is the action taking place? Is this a real event, or something hypothetical, like “I would have fed my dog” or “I could have fed my dog..”? Does this sentence just tell a story or does it also convey some weird emphasis? “My dog was fed a cookie by me,” for example, is a story about something that happened to my dog rather than a story about something I did.

- Learn the basic vocabulary. When I say ‘basic,’ I mean these words: I, to feed, dog, a, cookie. We need flashcards for all of these, and translations aren’t allowed, so let’s look at what these look like:

Four of these are relatively easy. You can just use pictures:

I to feed

dog cookie

Assuming all of these words are totally new to you, you’ll make 4-8 flashcards (Word – Picture, Picture – Word) for each of these words. You can find the base forms (to feed, for example) in your dictionary. Because you’re the one making them, you’ll remember that the verb you’re learning is “to feed” rather than “to eat,” and that the picture of the guy pointing to himself is “I,” rather than “He” or “Man.”

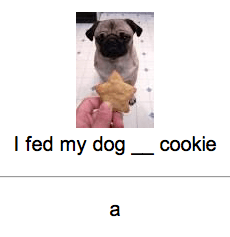

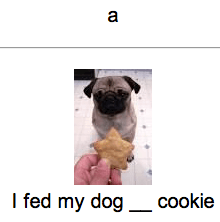

Now things get interesting. What does “a” mean, and how do we make a flashcard for it? If you did step #2, then you understand the whole story. You know that you had a cookie (There was no previously mentioned cookie, so we’re not using “the cookie”), you gave it to your dog, and he ate it. While “a” basically means “one” (in fact, that’s where it came from in old English), that’s not how we’re going to remember it. Instead, we’re going to remember the following definition: “a” is the word that fits into this sentence: I fed my dog __ cookie.

We’ll make two flashcards, which look like this:

When you review flashcard #1, you just need to supply the word “a.” When you review flashcard #2, you don’t need to spit out the whole sentence; you just need to remember that “a” is the word that goes before “cookie” in a sentence like that. It’s a fuzzy definition, and that’s OK. In time, as you encounter more sentences that use “a,” your brain will get a better sense for when and where it’s used, but your “a” will start with your dog and his cookie. Cards like these only work when you make them yourself. After all, you’re the one who’s spent time playing around with this sentence, so you’re the only one who’s going to benefit from this little reminder of what you’ve learned.

We’ll always use pictures, because they make memorization much easier. Even if our sentence is relatively abstract (Programming can be a complex endeavor), we’ll use some picture that’s vaguely related to the content of the sentence (i.e., a computer, or a programmer, or a blackboard full of equations).

What about “my”? We could learn “my” in the same way as we learned “a,” but we’re going to learn it in a different way. “My” is just what happens when you combine “I + Dog,” and we already know those two words. So we’ll learn “my” in the next step, when we play around with word formation.

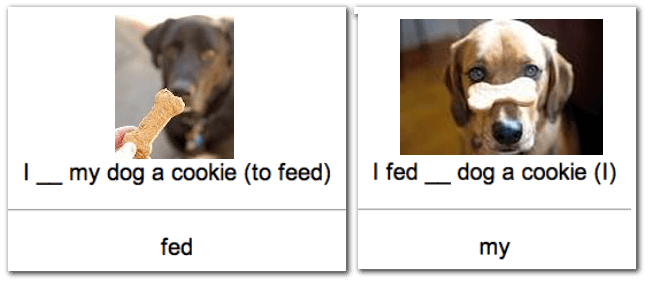

- Learn any changes in word-formation. Here’s where we learn “fed” and “my.”

To learn changes in word formation, we’ll give ourselves the example sentence and the root form of the word, like this:

Note that I’m switching out the pictures for each word. You don’t have to switch out the pictures, but in my experience, it works substantially better. New images mean that you’re going to form new associations, and I’ve found that this produces flashcards that are easier to learn and retain.

- Word order time. We need to know where each unit of the sentence goes. We’ll take a few chunks out of the sentence and try to reassemble them. These flashcards look like this:

These are four possible options (out of eight or so). If I were just starting with English, I might use this many (or perhaps even a couple more). If I’ve already learned a few sentences, 2-3 word order cards will be enough to help me remember where to place my objects, or whether “my” goes before or after “dog,” etc.

Because of the way all of these cards direct your attention to the various parts of the sentence, you get a great deal of mileage out of them.

Any time you write or encounter a new sentence and need to figure out who’s doing what to whom, or whether the action is occurring in the present or past, you’ll automatically recall the appropriate part of this dog/cookie story. If you do this with a few good sentences from each chapter in your grammar book, you’ll often find that when your book introduces you to a “new” concept, you already know something about it, because you’ve learned it from an earlier sentence.

Try it out and see how you like it. If something’s unclear, get in touch.